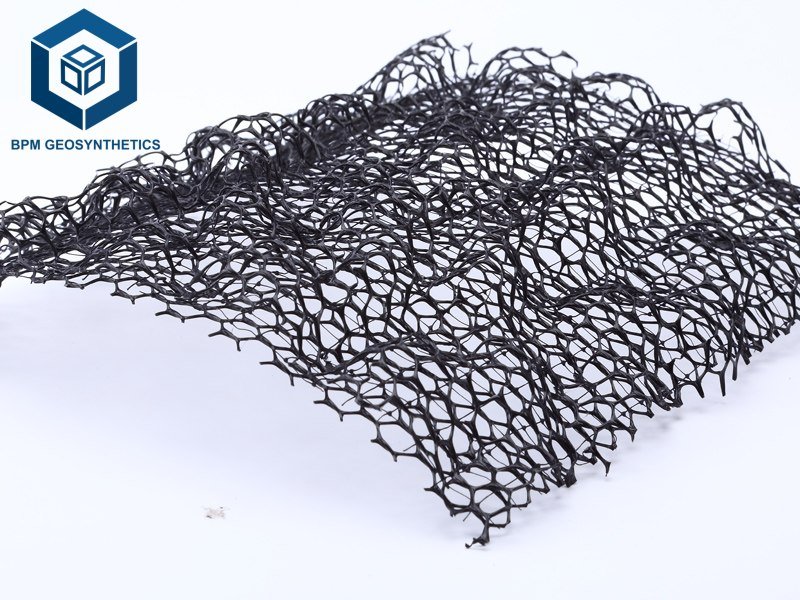

Geogrid Fabric is a geosynthetic material, primarily made from polymers like polyester, polypropylene, or high-density polyethylene. It is characterized by a rigid, open grid-like structure of intersecting ribs, forming large apertures. It is a high-strength reinforcing mesh used to strengthen and stabilize soil masses in civil engineering and construction projects. It is distinct from nonwoven geotextiles, which are primarily used for separation, filtration, and drainage.

1.What is Geogrid Fabric

BPM Geogrid fabric finds widespread applications in civil engineering and construction projects: it strengthens road and railway subgrades to reduce settlement and extend pavement lifespan, stabilizes slopes and embankments to prevent erosion and landslides, reinforces retaining walls and reinforced soil structures to enhance bearing capacity, supports foundations for buildings and industrial facilities in weak soil areas, and aids in soil reinforcement for landfills, airports, and port terminals—effectively addressing challenges posed by poor soil conditions and heavy load requirements.

2.What are Disadvantagaes Of Geogrid Fabric

Geogrid fabric, despite its wide use in geotechnical engineering, has distinct disadvantages that affect project economics, performance, and longevity. Below are its key drawbacks, organized by practical impact:

2.1High Initial and Operational Costs-Geogrid Fabric

Material costs are higher than traditional alternatives like gravel or natural fiber mats, especially for high-performance variants (polyester, glass-fiber).

Installation requires specialized labor, tensioning tools, and precision quality control, adding to project expenses.

Small-scale or low-budget projects often find it cost-ineffective due to the combined material and installation costs.

2.2 Vulnerability to Physical Damage-Geogrid Fabric

Sharp objects (rocks, roots, debris) can puncture or tear the fabric during laying, with small damages propagating under tension.

Improper tensioning (over-tightening or under-tightening) leads to structural failure or reduced load distribution efficiency.

Non-UV-stabilized geogrids degrade under sunlight, losing tensile strength and shortening service life in above-ground applications.

2.3Sensitivity to Harsh Environments-Geogrid Fabric

Aggressive substances (acidic/alkaline soils, petroleum products) break down the polymer structure, causing chemical degradation.

Extreme temperatures (freeze-thaw cycles, high heat) lead to deformation, brittleness, or softening of thermoplastic geogrids.

Organic-rich soils may promote biodegradation of certain geogrid materials, reducing durability.

2.4Limited Effectiveness in Poor Soil Conditions-Geogrid Fabric

Cohesive soils (clay) provide insufficient friction with smooth geogrids, leading to slippage and reduced reinforcement.

Saturated or weak organic soils (peat) fail to interlock with the grid, limiting load distribution and stability improvement.

Supplementary geosynthetics (e.g., geotextiles) are often required in problematic soils, increasing project complexity.

2.5Design and Compatibility Challenges-Geogrid Fabric

Precise engineering is mandatory to match geogrid properties (tensile strength, mesh size) with soil type and project loads.

Material mismatches (e.g., brittle glass-fiber geogrids in flexible pavements) cause performance failures.

Retrofitting existing structures is difficult due to poor bonding with old materials, leading to uneven load distribution.

2.6Long-Term Durability Uncertainties-Geogrid Fabric

Polymer-based geogrids suffer from oxidation and hydrolysis over time, gradually losing structural strength.

Biological growth (roots, fungi) causes deformation and accelerates material degradation.

Lack of standardized lifespan data makes long-term performance predictions unreliable, increasing project risk.

3.Installation Process:

3.1Site Preparation

Clear the installation area of debris, sharp rocks, roots, and vegetation to prevent geogrid punctures.

Level the soil substrate and compact it with machinery to ensure uniform bearing capacity, then grade according to design slopes or flatness requirements.

Remove excess moisture to avoid soil softening that could affect installation stability.

Material Inspection and Preparation

Check geogrid rolls for factory defects (tears, holes, uneven mesh) and confirm tensile strength, mesh size, and material type match project specs.

Unroll geogrid on a clean, flat surface near the site—avoid dragging over sharp edges to prevent abrasion.

3.2 Laying the Geogrid

Lay the geogrid in the direction of the primary load (e.g., along road length, parallel to slope contours) for optimal reinforcement.

Overlap rolls by 15–30 cm (per manufacturer guidelines) to ensure continuous load transfer, no gaps allowed.

Tension lightly with specialized tools to eliminate wrinkles—avoid over-tightening (risk of snapping) or under-tensioning (reduced efficiency).

3.3 Securing and Anchoring

Anchor edges (especially slopes/retaining walls) using backfilled trenches, steel stakes, or concrete footings to prevent slippage.

Secure overlapping sections with UV-resistant fasteners (clips, staples) or heat welding (for thermoplastics) to maintain structural continuity.

Space anchor points evenly (1–2 meters apart) and embed deeply enough to resist pull-out forces

3.4Covering and Compaction

Immediately cover the geogrid with specified fill (granular soil, gravel) to protect from UV damage and physical wear.

Add fill in thin, uniform 15–20 cm layers and compact each with light-medium machinery—avoid direct contact with heavy equipment.

Ensure thorough compaction without over-pressing, which could crush the mesh or weaken soil-geogrid interlock.

3.5Quality Control and Inspection

During installation, inspect for tears, shifts, or improper tensioning; repair small tears with geogrid patches and reposition misaligned rolls.

After covering with fill, verify the geogrid is fully encapsulated and the surface is even (no bulges/depressions).

Document key steps (photos, material batches, measurements) for compliance and future reference.

4.Summary

BPM Geogrid fabric has notable disadvantages affecting its practicality and longevity. It carries higher material and installation costs than traditional alternatives, requiring specialized labor and tools that make it cost-ineffective for small or low-budget projects. Vulnerable to physical damage, it can be punctured by sharp debris during installation, while non-UV-stabilized variants degrade under sunlight, losing tensile strength. Harsh environments—acidic/alkaline soils, extreme temperatures, or petroleum contaminants—trigger chemical degradation, shortening its service life. It performs poorly in cohesive, saturated, or weak organic soils due to insufficient friction and interlock, often needing supplementary geosynthetics. Precise engineering is mandatory; material mismatches or flawed design cause underperformance. Long-term durability is uncertain, with oxidation, hydrolysis, and biological growth further compromising structural integrity.